Dirac spinor

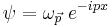

In quantum field theory, the Dirac spinor is the bispinor in the plane-wave solution

of the free Dirac equation,

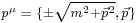

where (in the units  )

)

is a relativistic spin-1/2 field,

is a relativistic spin-1/2 field, is the Dirac spinor related to a plane-wave with wave-vector

is the Dirac spinor related to a plane-wave with wave-vector  ,

, ,

, is the four-wave-vector of the plane wave, where

is the four-wave-vector of the plane wave, where  is arbitrary,

is arbitrary, are the four-coordinates in a given inertial frame of reference.

are the four-coordinates in a given inertial frame of reference.

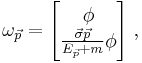

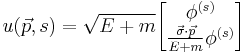

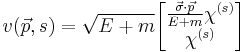

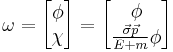

The Dirac spinor for the positive-frequency solution can be written as

where

is an arbitrary two-spinor,

is an arbitrary two-spinor, are the Pauli matrices,

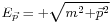

are the Pauli matrices, is the positive square root

is the positive square root

Contents |

Derivation from Dirac equation

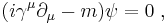

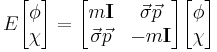

The Dirac equation has the form

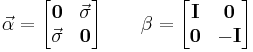

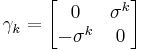

In order to derive the form of the four-spinor  we have to first note the value of the matrices α and β:

we have to first note the value of the matrices α and β:

These two 4×4 matrices are related to the Dirac gamma matrices. Note that 0 and I are 2×2 matrices here.

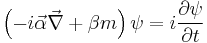

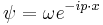

The next step is to look for solutions of the form

,

,

while at the same time splitting ω into two two-spinors:

.

.

Results

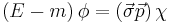

Using all of the above information to plug into the Dirac equation results in

.

.

This matrix equation is really two coupled equations:

Solve the 2nd equation for  and one obtains

and one obtains

.

.

Solve the 1st equation for  and one finds

and one finds

.

.

This solution is useful for showing the relation between anti-particle and particle.

Details

Two-spinors

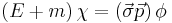

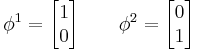

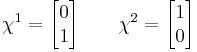

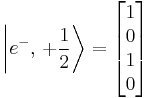

The most convenient definitions for the two-spinors are:

and

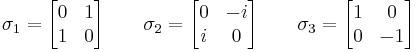

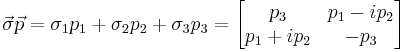

Pauli matrices

The Pauli matrices are

Using these, one can calculate:

Four-spinor for particles

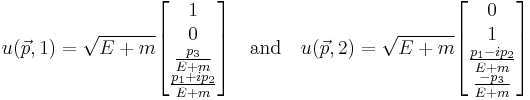

Particles are defined as having positive energy. The normalization for the four-spinor ω is chosen so that  . These spinors are denoted as u:

. These spinors are denoted as u:

where s = 1 or 2 (spin "up" or "down")

Explicitly,

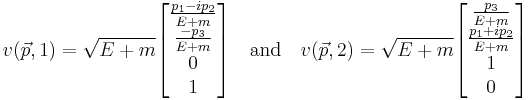

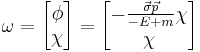

Four-spinor for anti-particles

Anti-particles having positive energy  are defined as particles having negative energy and propagating backward in time. Hence changing the sign of

are defined as particles having negative energy and propagating backward in time. Hence changing the sign of  and

and  in the four-spinor for particles will give the four-spinor for anti-particles:

in the four-spinor for particles will give the four-spinor for anti-particles:

Here we choose the  solutions. Explicitly,

solutions. Explicitly,

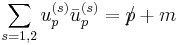

Completeness relations

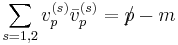

The completeness relations for the four-spinors u and v are

where

(see Feynman slash notation)

(see Feynman slash notation)

Dirac spinors and the Dirac algebra

The Dirac matrices are a set of four 4×4 matrices that are used as spin and charge operators.

Conventions

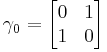

There are several choices of signature and representation that are in common use in the physics literature. The Dirac matrices are typically written as  where

where  runs from 0 to 3. In this notation, 0 corresponds to time, and 1 through 3 correspond to x, y, and z.

runs from 0 to 3. In this notation, 0 corresponds to time, and 1 through 3 correspond to x, y, and z.

The + − − − signature is sometimes called the west coast metric, while the − + + + is the east coast metric. At this time the + − − − signature is in more common use, and our example will use this signature. To switch from one example to the other, multiply all  by

by  .

.

After choosing the signature, there are many ways of constructing a representation in the 4×4 matrices, and many are in common use. In order to make this example as general as possible we will not specify a representation until the final step. At that time we will substitute in the "chiral" or "Weyl" representation as used in the popular graduate textbook An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory by Michael E. Peskin and Daniel V. Schroeder.

Construction

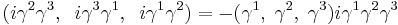

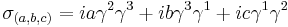

First we choose a spin direction for our electron or positron. As with the example of the Pauli algebra discussed above, the spin direction is defined by a unit vector in 3 dimensions, (a, b, c). Following the convention of Peskin & Schroeder, the spin operator for spin in the (a, b, c) direction is defined as the dot product of (a, b, c) with the vector

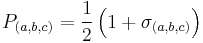

Note that the above is a root of unity, that is, it squares to 1. Consequently, we can make a projection operator from it that projects out the sub-algebra of the Dirac algebra that has spin oriented in the (a, b, c) direction:

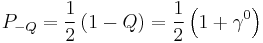

Now we must choose a charge, +1 (positron) or −1 (electron). Following the conventions of Peskin & Schroeder, the operator for charge is  , that is, electron states will take an eigenvalue of −1 with respect to this operator while positron states will take an eigenvalue of +1.

, that is, electron states will take an eigenvalue of −1 with respect to this operator while positron states will take an eigenvalue of +1.

Note that  is also a square root of unity. Furthermore,

is also a square root of unity. Furthermore,  commutes with

commutes with  . They form a complete set of commuting operators for the Dirac algebra. Continuing with our example, we look for a representation of an electron with spin in the (a, b, c) direction. Turning

. They form a complete set of commuting operators for the Dirac algebra. Continuing with our example, we look for a representation of an electron with spin in the (a, b, c) direction. Turning  into a projection operator for charge = −1, we have

into a projection operator for charge = −1, we have

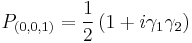

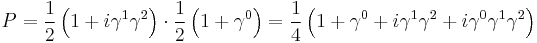

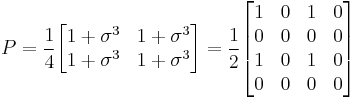

The projection operator for the spinor we seek is therefore the product of the two projection operators we've found:

The above projection operator, when applied to any spinor, will give that part of the spinor that corresponds to the electron state we seek. Therefore, to write down a 4×1 spinor we take any non zero column of the above matrix. Continuing the example, we put (a, b, c) = (0, 0, 1) and have

and so our desired projection operator is

The 4×4 gamma matrices used in Peskin & Schroeder (Weyl representation) are

for k = 1, 2, 3 and where  are the usual 2×2 Pauli matrices. Substituting these in for P gives

are the usual 2×2 Pauli matrices. Substituting these in for P gives

Our answer is any non zero column of the above matrix. The division by two is just a normalization. The first and third columns give the same result:

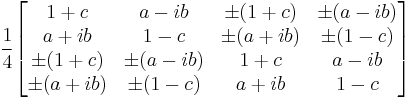

More generally, for electrons and positrons with spin oriented in the (a, b, c) direction, the projection operator is

where the upper signs are for the electron and the lower signs are for the positron. The corresponding spinor can be taken as any non zero column. Since  the different columns are multiples of the same spinor.

the different columns are multiples of the same spinor.

See also

References

- Aitchison, I.J.R.; A.J.G. Hey (September 2002). Gauge Theories in Particle Physics (3rd ed.). Institute of Physics Publishing. ISBN 0750308648.

- Miller, David (2008). "Relativistic Quantum Mechanics (RQM)". pp. 26–37. http://www.physics.gla.ac.uk/~dmiller/lectures/RQM_2008.pdf